Here are the most interesting things I’ve been reading, watching, and listening to in the last month.

If you are between 16 and 21 and based in Europe, applications are now open for Patch, an accelerator for startups and other ambitious projects every summer in Dublin. They rely heavily on referrals from alumni to select future cohorts, so if you feel there is a compelling reason why I should tilt the scales in your favour, you can email sam [at] thefitzwilliam [dot] com.

Merry Christmas!

Blogs

Are you looking for the perfect gift for your soon-to-be spouse? For a mere $25,000, you can buy your very own Qing Dynasty wedding bed. If that is out of budget, for only $731, you can buy statistically representative ‘domestic sludge’ used as a reference material by the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

Speaking of gift advice, here is Lauren Gilbert’s gift-giving guide for economic policy nerds. My favourite entry here is the brutalism calendar, which sadly has sold out for 2025. Maybe one day I’ll write up my own gift-giving guide; a recent winner has been a six-variable graph of Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow.

Laura Deming on the rage of research. And, found via the comments section, the Nintil rules for research. Elsewhere, Nintil rounds up links.

You may have seen a headline a few years ago about how the French Scrabble Championship was won by a man who doesn’t speak French. He has now repeated the feat, and become world champion in Spanish Scrabble, despite not speaking Spanish either. He apparently doesn’t like reading books either.

Congratulations to the new cohort of Emergent Ventures winners. I look forward to the autobiography of Morris Chang being translated.

Speaking of long-awaited biographies, a biography of Roger Penrose has been released…

There are many helplines for people struggling with their mental health, studies, or career to seek advice. But what if you’re already beautiful, smart, and successful, and you want to give people advice? Your prayers have been answered!

You may prefer different large language models for different uses, but it can be difficult to tell whether preference for one over another is just a placebo. The Chatbot Arena allows you to prompt multiple anonymous LLMs at the same time and rate which response is most helpful. You can also see a leaderboard of the rankings other people have made. Currently, Gemini and GPT-4o are tied for first place – although perhaps that is because they are the most sycophantic.

One of the most famous unsolved problems in mathematics is the moving sofa problem, which is the problem of finding the largest possible “sofa” which can be manoeuvred around an L-shaped corridor of width 1. The conjectured best possible solution is a shape called ‘Gerver’s sofa’, with an area of ~2.2195. A mathematician at Yonsei University in Seoul has claimed to have solved this problem by proving that Gerver’s sofa is in fact optimal. Huzzah!

Gavin Leech reviews Bristol. Elsewhere, he reviews the biggest scientific and mathematical breakthroughs of 2024.

There is a new documentary out about the legendary music producer Brian Eno, which is the first feature-length film to contain a generative AI component (the film is subtly different at each screening). So far, I haven’t been in any cities where it has been showing, but I hope to be soon. Here is a full list of screenings.

Massachusetts now has occupational licensing for fortune tellers. You can be fined for failing to have a license for fortune telling, or for merely “pretend” (?) fortune telling.

While dictator of Libya, Muammar Gaddafi bankrolled a group of Maltese funk bands to create a new music genre praising his regime. And it’s pretty groovy!

Best of Wikipedia: List of territory purchased by a sovereign nation from another sovereign nation. Some of these are famous, like the Louisiana Purchase, the purchase of Alaska from Russia, or – if you’re Scottish – the purchase of the Hebrides from Norway. But did you know that the United Kingdom purchased Singapore from the Johor Sultanate in 1824 for $60,000 Spanish (?) dollars? Or that Denmark sold its holdings in India to the UK in 1845? And can you guess what the most recent land purchased from one country by another is?

Best of Twitter: A GPU organ which plays music acoustically by controlling the speed of the fans. And some highbrow humour about the composition of recent Y Combinator cohorts… Finally: a thread of timeless academic papers which transcend disciplines. Can you tell I just figured out where bookmarked tweets go?

The pipeline of blog posts, usually written by people called Sam, becoming official British government policy remains alive and well.

The field of AI safety has become large enough to have different subfields and specialities. One of these, closely associated with Anthropic, is mechanistic interpretability (“MechInterp”), which uses various tools to try to interpret what AI systems are ‘thinking’. MechInterp has come on in leaps and bounds in recent years, driven by various prodigies such as Chris Olah and Neel Nanda. Another area is ‘evals’, or evaluating whether an AI system has reached certain benchmarks for intelligence and capabilities. Presumably evals would be a key part of any effort to regulate AI. There are a lot of nuances, like how assessing whether a language model has reached a certain capability is highly sensitive to the exact prompt used. Some of these are hilarious: The performance of LLMs on benchmarks can shift by percentage points if you use square brackets instead of round brackets in the prompt, or if you end it by saying ‘I’ll tip $100 for a good answer’! Here is Apollo Research on the need for a new science of evals.

Elliot Fosong is procrastinating submitting his PhD by evaluating the favourite image of the open-source language model Molmo. He ran pairwise comparisons and aggregated those scores into an overall ranking with an algorithm similar to the Elo system widely used to create chess rankings. For fun, you can then test various hypotheses about the model’s preferences, like whether they are transitive (if an AI says it prefers painting A to painting B, and painting B to painting C, will it prefer painting A to painting C?).

Another question Elliot has recently asked: What is the most controversial film of all time?

Elliot, by the way, is a reader of this blog, and left a thoughtful comment on the most recent links post which is worth highlighting:

> How did the Hanseatic League affect mediaeval European trade?

Strongly recommend a visit to Lübeck (and Hamburg, and Hanseatic black sheep Bremen). Besides the beautiful brick architecture and tasty Marzipan, Lübeck is full of Hanseatic history and is home to the European Hansemuseum (https://www.hansemuseum.eu/en/). One of the best museums I've ever been to. It gives a lot of details about how the Hanseatic League worked and what exactly was being traded and with whom. I've never seen a museum with so many statistics before. It's like walking around an economics textbook (in a fun way).

They have a cool customised tour feature where you pick a city-of-interest from a list (including Edinburgh) and a special interest (e.g. 'shipbuilding'), and as you go through the museum you scan a card which makes the exhibits give special information about your chosen topics.

And if you do go to Hamburg, don't miss Miniatur Wunderland.

As if there’s a way to walk around an economics textbook which wouldn’t be fun!

Xenophon, another student of Socrates, also wrote philosophical dialogues, and is one of the main reasons we know Socrates was an actual person who existed. He also wrote one of the classics of Greek literature, The Education of Cyrus, an account of the upbringing and life of Cyrus the Great, founder of the First Persian Empire. Here is a review.

Dynomight on arithmetic as an underrated world-modelling technology.

I recently learned that rubber gloves were invented by a surgeon, William Halstead, in 1889, in order to impress a nurse he had a crush on (the ‘gloves of love’). She later became his wife. Halstead literally launched one of the most important public health revolutions in history to get a girlfriend – what’s your excuse?

A review of William Dalrymple’s delightful travelogue In Xanadu, which he wrote when he was 22 (!) and which contains two major original archaeological discoveries (!!). Privately-educated British men really do have a stranglehold on the ‘Swashbuckling Adventures in the Orient’ genre.

Tim Urban on what it was like to watch the SpaceX Super Heavy launch in person.

Rebecca Lowe, one of the most British people I know, reports from her first ice hockey match in America. She mentions the phenomenon of ‘pulling the goalie’. To be honest, I’m not sure what this means, but I do know that there is some statistical research on this topic (Cowen’s second law!). It concludes that ice hockey teams pull the goalie far too infrequently, to avoid looking stupid if the gambit doesn’t work –see Malcolm Gladwell’s podcast.

Henry Oliver on his favourite books of 2024. Elsewhere, Henry has a tirade against the philistine supremacy.

Here’s a (seemingly) simple question: While Biden was president, did inflation make the average American poorer? Zach Mazlish crunches the numbers convincingly and concludes that the answer is ‘yes’.

Andrew Batson reviews the best books he read in 2024. From this, Eileen Chang’s collected essays from pre-revolutionary China are near the top of my reading list.

What Henrik Karlsson learned working in an art gallery. A great piece about taking pride in one’s work.

Books

Maxwell Rosenlicht, Introduction to Analysis. I’ve felt bad about never having taken a real analysis course since Lee Kuan Yew’s grandson bullied me about it on Twitter. So, I’m taking one now. I am in no position to evaluate this book, because I found most of it incomprehensible. One odd thing about it is that the theorems it relies on, it never seems to name. For example, the author discusses Banach’s fixed point theorem (p. 178) and Young’s theorem (p. 202), without mentioning either’s common name. Is this supposed to make it easier for students? If I don’t have memorable names to associate certain results with, it all blends together in my head.

This book’s exercises have no solutions, which is good and bad. Problems with solutions risk teaching you the bad life advice that all problems can be solved, that all problems are worth solving, and that problems can all be solved using the techniques learned in the corresponding chapter. On the other hand, if you just read the book and think about the exercises yourself, the feedback loop is so loose that I’m in awe of anyone who can learn this way.

If you do read this book, make sure to get the 2013 reprinting. The text has been unchanged since 1968, but I found the lettering from the older edition to be so difficult to read that I eventually gave up.

Benjamín Labatut, The MANIAC. Fabulous! This is a lightly fictionalised biography of John von Neumann, written in the style of a novel. I read precious few novels, but novels about the history of science might be my favourite subgenre. I enjoyed this a lot more than Ananyo Bhattachraya’s The Man From the Future, a von Neumann biography which came out in 2021. That book is competently executed, and so far as I know does a fine job covering the relevant science. I had a hard time putting my finger on why it didn’t emotionally stick with me until I saw this Goodreads review from Jason Furman:

I was also disappointed. [The Man From the Future] purports to be a biography of John von Neumann… but it felt like half or possibly even more of it was devoted to developments that happened before, during, and often after von Neumann. For example, the chapter on quantum mechanics does much more to retell familiar stories of Heisenberg and Schrödinger than it does to tell about van Neumann’s contributions. The chapter on replicators has a little von Neumann but it seems like almost more on Conway, Wolfram and several others who followed him.

After the first chapter (which is biography) it is basically seven essays on the amazingly wide range and rapidly developing and changing topics von Neumann made massive contributions to (the theory of mathematics, the unification of different models of quantum mechanics, the design of nuclear weapons, the birth of programmable computers, game theory, RAND, and replicating models).

Many of the essays are good but they don't quite hit the mark in explaining von Neumann’s ideas (which may be very hard to explain), sometimes have long sections that tell overly familiar stories or overly tangential ones, and does not weave together the life and discoveries.

That said, von Neumann is truly amazing and reading it all together is exciting and worthwhile.

Furman was the chairman of Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisors, but more importantly, he has an excellent Goodreads profile to which he posts many thoughtful reviews.

Karl Ove Knausgård, Spring. This is volume three in the ‘Seasons Quartet’, four short novels written in the form of a letter from Knausgård to his newborn daughter. It’s similar to the My Struggle series, which are among my favourite novels. Make sure you get the paperback – the novel is a joint aesthetic experience between the art and the prose.

Julian Havil, The Irrationals. A reasonably challenging maths text from Princeton Science Library, the same series which I lauded recently for their publication of Elements of Mathematics. The author writes about the history of famous irrational mathematical constants, associated concepts, and the proofs of their irrationality and transcendental-ness (transcendentality?). Irrational numbers seem to share with the primes the quality that children can pose questions about them that the greatest mathematicians in the world cannot answer. For example, it’s still not known for sure whether π+e is irrational. Over the Christmas holidays, please enjoy this piano jingle about Fourier’s proof of the irrationality of Euler’s number.

Quentin Tarantinto, Cinema Speculations. A collection of fairly meandering essays about Tarantino’s upbringing and filmic influences. This book contributes to my impression that the 1980s were dismal in American cinema (in stark contrast to the grungy but interesting 1970s). If you’ve ever seen any of Tarantino’s films, you can tell how influenced he has been by the ‘Blaxploitation’ genre. Overall, I was struck by just how few of these films I’ve ever seen, and how few of the names I’ve ever heard. My favourite section was the speculations about what Taxi Driver would have been like if Brian De Palma hadn’t turned down the opportunity to direct it.

Micheal Wood, In the Footsteps of Du Fu, China’s Greatest Poet. One of the crown jewels of Chinese civilisation is the poetry of the Tang Dynasty, and its most famous practitioner was Du Fu (712–770 AD). I find it dispiriting how few people in the West have even heard of Du Fu; Michael Wood takes the view that only Shakespeare and Dante can even be spoken of in the same breath regarding their influence on global literature.

I’ve been in the midst of exams the last few weeks, and this book was a delightful palette cleanser. Chinese has no tenses, no gender, and no definite or indefinite articles in the sense that English does, which makes translation especially ambiguous. Perhaps the glories of Tang poetry will remain forever inaccessible to a pasty Irishman such as myself, but here is a translation I liked of ‘Spring Landscape’ (春望):

The country is broken but the mountain and river remain,

Inside the city, the grass and wood grow deep.

The flowers seem to be weeping,

The birds appear to grieve at the sight of departure.

The war flames rage for three months,

A letter from home would be worth much gold.

My white hair is scratched so short

That it can no longer hold the weight of a hairpin

Richard Campbell, Lanning Sowden, Paradoxes of Rationality and Cooperation: Prisoner’s Dilemma and Newcomb’s Problem. I wish more books were in this format of collected papers with annotated notes and an introduction. I assume this doesn't happen more often partly for copyright reasons. Having said that, in 2024 this book is insanely niche. Many better and more up-to-date volumes exist about the prisoner's dilemma and Newcomb's problem, including the Cambridge University Press classic philosophical arguments series. So you'd have to intrinsically care about the intellectual history of these topics from 1969 to 1985...

In case you’re just joining us and have no idea what I’m talking about, here is the summary of the basic setup of Newcomb’s paradox from Wikipedia:

There is a reliable predictor, another player, and two boxes designated A and B. The player is given a choice between taking only box B or taking both boxes A and B. The player knows the following:

Box A is transparent and always contains a visible $1,000.

Box B is opaque, and its content has already been set by the predictor:

If the predictor has predicted that the player will take both boxes A and B, then box B contains nothing.

If the predictor has predicted that the player will take only box B, then box B contains $1,000,000.

The player does not know what the predictor predicted or what box B contains while making the choice.

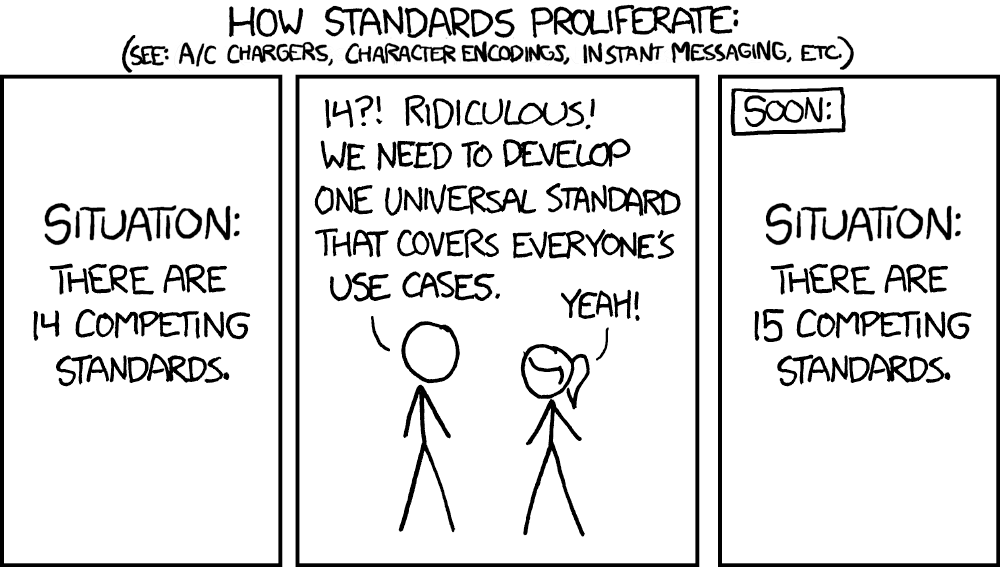

Arif Ahmed, Newcomb’s Problem. There’s an old mean joke which has it that “Physicists have speculated that information can escape even from a black hole. The same has yet to be proven for an edited volume.” But this is actually quite a nice book – if you only read one piece of serious philosophy about Newcomb’s problem, I recommend it be this. Chapter 10 analyses Newcomb’s problem using causal graph notation, which you may be familiar with due to the influence of Judea Pearl. That reframes the debate as being about how exactly “agency” or “free will” should be represented on a causal graph, rather than about which version of decision theory is actually “true”. The author of that chapter, Reuben Stern, introduces a new version of decision theory, interventionist decision theory, which behaves better under causal graphs. This is all getting to be above my paygrade, but when I see new principles or theories of rational choice being introduced to deal with edge cases like Newcomb’s problem, I can’t help but think of this classic XKCD comic:

Papers

Evan Miller, Adding Error Bars to Evals: A Statistical Approach to Language Model Evaluations. This is a preprint about the need to apply the basics of statistical hypothesis testing to AI evals. Apparently, it’s not even common practice for frontier AI labs to report standard errors when they release the results of an eval. When an AI company claims to have reached a certain milestone, we don’t even have p values for how likely it is such a result would be observed if the null hypothesis were true. There is apparently still a lot of alpha in having an undergraduate level of knowledge in a different field and applying it elsewhere: this paper comes from an Anthropic researcher, but is essentially just undergraduate econometrics. It looks like Appendix A is just restating the results of Halbert White’s legendary 1980 Econometrica paper, which gave us robust standard errors.

José Luis Bermúdez, Prisoner’s dilemma and Newcomb’s problem: why Lewis’s argument fails. David Lewis wrote a famous short paper in 1979 arguing that the prisoner’s dilemma and the Newcomb problem are actually the same thing. This conclusion came to be pretty widely accepted, but here is a moderately convincing rebuttal.1

A girl once asked me on a first date whether I am a one-boxer or a two-boxer in the Newcomb problem. I wish this was one of those “and that’s how I met my wife” stories, but actually, there wasn’t even a second date, for what I hope were unrelated reasons.

J.L. Mackie, Newcomb’s Paradox and the Direction of Causation. J.L. Mackie was an Australian philosopher probably best known for defending moral error theory, which is the view that moral statements do express meaningful propositions, but all of those propositions happen to be false. He once wrote this little-known paper about Newcomb’s problem, which is one of a family of arguments which say that the problem is ill-posed, because we haven’t been told how the predictor came to be so reliable (and that the correct answer differs based on what this explanation is). It’s funny to see what contemporary examples authors choose which date their work. In this case, Mackie discusses the strategic implications of Israel’s then-current occupation of the Sinai peninsula after the Yom Kippur War…

Philip Pettit, Newcomb’s Problem is an Unexploitable Prisoner’s Dilemma. An addendum to the original Lewis argument about prisoner’s dilemmas being Newcomb problems, which says that the situations are relevantly different enough that his conclusion does not mean that sufficiently similar prisoners in a prisoner’s dilemma should cooperate, even if one-boxing were the correct solution for Newcomb. I didn’t quite follow the central argument here, but I feel that if I read anything more about this topic, my brain will turn to mush.

Al Seckel, Russell and the Cuban Missile Crisis. One unexpected figure in the history of the Cuban missile crisis was the 90-year-old Bertrand Russell, who in addition to being a public intellectual was the first president of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. During the Crisis, Russell exchanged telegrams with John F Kennedy, Nikita Khrushchev, Harold McMillan, and U Thant. Khrushchev quickly wrote back to Russell, suggesting the possibility that they have a ‘top-level meeting’. It seems extremely implausible that Bertrand Russell was counterfactually responsible for averting nuclear armageddon, but I am mostly interested in this episode from the perspective of how remarkable it is that an elderly academic philosopher was taken seriously by the most powerful politicians in the world during a period almost escalating to global war. How times have changed.

Podcasts

Friend-of-the-blog Zach Mazlish has appeared on the Macro Musings podcast!

Richard Butler, a relatively obscure Australian diplomat, is responsible for the extension of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, and for the passage of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. Normally treaties are enacted in perpetuity, but the NPT was sufficiently controversial that by default it needed to be extended after 25 years to not lapse. Here he is being interviewed by Joe Walker. This is genuinely frontier oral history about nuclear weapons – bravo!

Russ Roberts and Tyler Cowen discuss a masterpiece of Russian literature, Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate.

Speaking of the Russians: Stephen Kotkin on what he learned from writing three volumes of biography of Stalin. Here is an excerpt:

COWEN: Do you think Georgian blood feud culture influenced Stalin at all in this?

KOTKIN: [T]here were a lot of Georgians and there’s one Stalin. People argue that he got into fights in the schoolyard, and that the fights were nasty, and therefore he became a certain type of person. They argue that his father beat him, and therefore he became a certain type of person. The problem with arguments like that, Tyler, is that I got into fights in the schoolyard when I was his age. People beat me up… My father also disciplined me with the proverbial belt when I got out of hand. I didn’t go on to collectivize agriculture… I refuse to use sources that were retrospective. If you survived the Stalin collectivization terror, and you wrote a memoir, you looked back on those days in the schoolyard, that Georgian revenge culture, and you said, “Oh, I remember when he was 11, and he put the cat in the microwave. I knew right then that we were all going to die.”

Overall, my top three podcast episodes from 2024 were this one about Stalin, Richard Butler on nuclear arms reduction treaties, and Daniel Yergin on the history of oil.

Dwarkesh Patel chats with Spencer Greenberg about human evolution and its lessons for AI.

Gwern Branwen, the pseudonymous internet polymath, has made his first podcast appearance. The video version features a creepy AI avatar to preserve his anonymity.

OpenAI has a famously complicated legal structure, in which a non-profit controls a for-profit business, in which Microsoft is the largest investor. The leadership has gradually been eroding this structure – Sam Altman now has a direct financial stake in the company, and is attempting to remove the non-profit’s control. Here is an interview with an expert on non-profit law about these legal wranglings.

Pavin Krishna on the political economy of Indian trade liberalisation. It’s tempting to think that, if free trade is good, then any regional free trade agreement is also good. However, unilaterally liberalising trade has the effect of shifting trade toward those less protected markets, which may or may not be the place where it makes the most sense for certain goods to be produced. And the more trade there is between certain countries, the greater incentive that ‘rent-seekers’ have to preserve such an arrangement. This episode helped me better understand the debates between Jacob Viner and John Maynard Keynes surrounding trade, and the creation of the Bretton Woods system and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. Good job!

The Marginal Revolution podcast on the crime wave of the 1970s. And the economics of insurance markets.

Sam Bowman articulates the problems with the British economy.

Rick Rubin interviews (?) Richard Feynman.

From the Economist: an informative series about the rise of Narendra Modi. I don’t think this one was quite as good as their series about Xi Jinping.

The Rest is History on the political resurrection of Richard Milhous Nixon. This podcast series gives a more up-to-date view on the Chennault affair I alluded to in last month’s links post, which is the theory that Henry Kissinger convinced the South Vietnamese delegation to withdraw from peace talks in Paris in 1968 to torpedo the Democrats’ reelection chances. Supposedly the latest scholarship indicates that President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu would never have accepted Lyndon B Johnson’s proposed peace deal, and always thought he would get a better bargain under Nixon. But I don’t fully understand the view Dominic Sandbrook is laying out here. Is he saying that it’s just a coincidence that the South Vietnamese delegation announced they were withdrawing from negotiations just a few days before the 1968 election? (Note that Nixon won the popular vote by a very narrow margin.) In any case, I was too quick to accept the narrative of the Ken Burns series. It’s on my to-do list to make a public mistakes page, and this will be on it.

The 99% Invisible series about the influence of The Power Broker has come to a close. I can report that The Power Broker is as good as everybody says it is.

Very Bad Wizards on the uses and abuses of the cognitive reflection task.

Henry Oliver and Marion Turner on why we’re living in Geoffrey Chaucer’s world.

Steven Spielberg on Desert Island Discs. I learned from this podcast that Steven Spielberg’s dad was more interesting than his son. Arnold Spielberg was an electrical engineer who rose to become the head operator for Allied radio communications in the Burma and China campaigns. While working at General Electric, he helped invent the GE-225 mainframe computer, which Bill Gates once credited for the existence of the Windows operating system – remarkable!

Zena Hitz on reading the Great Books.

How did Ovid change poetry?

Rasheed Griffith gives you a guided tour of the origins and philosophy of Jamaican Reggae.

Music

Yellowjackets, Yellowjackets. The debut album by a great American jazz fusion band. ‘Matinee Idol’ has been stuck in my head for weeks. Great slap bass on display.

Beethoven, Symphony No. 7 in A Major. This one is a fair bit more rhythmic than Beethoven’s other symphonies; I found myself lightly bouncing up and down in my chair while listening. One of the most famous quotes in classical music is Richard Wagner describing Beethoven’s 7th as the “apotheosis of the dance”. I hope one day I’ll know enough to be able to report back a full ranking – Beethoven is the origin of superstition about composers dying before they finish their 10th symphony. I heard this being performed this month by the Hungarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, who were accompanied by the 21-year-old rising star piano soloist Jeneba Kanneh-Mason. Here she is playing Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2.

Duke Ellington, The Nutcracker Suite. I thought there were no major Ellington albums I had never listened to before, but I didn’t know about this. This arrangement was made in collaboration with Billy Strayhorn, and if I’m not mistaken, this is the only album where he’s credited on the cover. Strayhorn was immortalised in jazz when his directions to Ellington on how to reach his apartment from Manhattan (“take the ‘A’ train”) became the title of a jazz standard. I’m not much of a ‘Christmas music’ person, but this may be my new favourite festive album.

Antonín Dvořák, Symphony No. 9 in E Minor. This is the famous ‘New World’ symphony Dvorak composed after visiting America for the first time, giving his musical impressions of the place (the subtitle is ‘From the New World’). Supposedly the rhythms are influenced by African-American and Native American folk music (incidentally, Dvořák said that African music reminded him of Scottish folk ballads). There are two types of men: Those who first think of Dvořák as a composer, and those who first think of the alternate keyboard layout. I think you can guess I am the latter.

Films

Ken Burns, The Vietnam War. At long last, I have finished this series. The tenth and final episode is incredibly moving. It even goes into Maya Lin’s design for the Vietnam War memorial on the National Mall in Washington D.C., which is (in my opinion) very tasteful. I’ve visited it a few times, and one of the times I was there, I saw that someone had left a copy of ‘McNamara’s Folly’ in front, which, if you’re familiar with the subject matter, is the most highbrow protest I’ve ever seen. On the whole, I’m glad I watched the whole series, even if it is overly long and drawn out in the middle. Before watching episode eight, I knew absolutely nothing about the US incursion into Cambodia to destroy Viet Cong base camps. It’s wild that, even though Nixon in principle ran for president on a platform of ending the Vietnam War, as late as 1970, an entirely new country was being drawn into the war.

Charles Vidor, Gilda. It’s remarkable how little effort you could get away with putting into setting in classic Hollywood films. Is there a single full sentence spoken in Spanish in this film supposedly set in Buenos Aires? I was pleased to find out I already recognised one of these scenes, the famous hair flick from Rita Hayworth, which is played for the prisoners in The Shawshank Redemption. Hayworth is also the woman on the poster under which Andy Dufresne escapes from prison. For me, this was a 3/5 film, and taking the mickey with the designation of ‘classic’.

Alfred Hitchcock, Rear Window. A true masterpiece. I’m glad I waited to see this until it was showing in a cinema near me – I had the experience of watching the people sitting on either side of me both, simultaneously and independently, bite their knuckles from the suspense!

Alfred Hitchcock, Dial M for Murder. Certainly this had much less of an effect on me than Rear Window or Vertigo; the characters and their motivations are much less believable. It came out the same year as Rear Window and also co-stars Grace Kelly, so it suffers in comparison, but for 1954, it’s still a fun and impressive achievement. I suspect the play from which it was adapted was better.

Akira Kurosawa, Seven Samurai. Bring back film intermissions! The cinematography is excellent, especially any scene on horseback or in the mud. But, for me, this doesn’t reach the heights or the humour of the opening scene in The Bad Sleep Well. For my next Kurosawa, I will probably look to the films with a modern setting rather than about samurai.

Edward Berger, Conclave. Based on the book by the British historical novelist Robert Harris. This is the only new release I’ve seen in the last year and a half other than Dune Part II and Napoleon. I’m starting to think even that rate is too high, because all of them were mediocre. If I had not been watching this film with a group of friends, I would have walked out. I love The Two Popes, which to me achieves everything Conclave was trying to achieve more effectively, including the depiction of the Sistine Chapel and the papal election process.

Friedrich Murnau, Nosferatu. A silent masterpiece of German Expressionism from 1922. The director didn’t have permission to adapt Bram Stoker’s novel, so Count Dracula becomes ‘Count Orlock’, and Jonathan Harker becomes ‘Thomas Hutter’. As a modern viewing experience, this was painful. The framerate is so low as to not even produce an illusion of movement. Toward the end, I couldn’t even follow the plot; is Professor Sievers (the stand-in for Van Helsing) supposed to have any causal influence on the story, or is he just there for pointless cutaways? All I can say is: I’m glad I watched this as a piece of cinema history.

I’ve spent the last few weeks tearing my hair out over the lack of established convention for whether it should be spelt ‘prisoner’s dilemma’ or ‘prisoners’ dilemma’ (and indeed, whether the term should be capitalised). Is the dilemma faced by one prisoner, or by both of them?!

the best present

Thanks for this whole post and for sharing that "If I don’t have memorable names to associate certain results with, it all blends together in my head"! I've been using Blitzstein & Hwang's probability textbook for teaching, and one of the many things I like about it is that they go out of their way to use (and sometimes invent) memorable names for theorems. :)