Here are the most interesting things I read, listened to, and watched in April.

I apologise that the post is late – I’m currently in the midst of exams, so it’s a small miracle that it exists at all.

My free subscriptions to The Economist and Financial Times are soon to expire, and I’m not sure if I’ll renew either of them. Please send me any favourite articles you have from either, so I can include them in next month’s post.

Speaking of The Economist, if you’ll permit me a grumble, they might honestly have the most scammy marketing tactics of any company I’ve interacted with in years. To unsubscribe required speaking to a specific individual, who then insisted against my wishes on subscribing me to one of their newsletters, which (because I’m no longer a subscriber) it’s impossible to unsubscribe from. I still get these emails every day, and they use various tactics to evade my spam filter. I’ve also now spoken to several Economist employees who said that they would escalate my case to management, and then ghosted me. Bagehot wouldn’t have stood for this!

For more links, you can use my invite code to join Lynkmi. My friend Matt Clancy found out about Lynkmi through one of these blogs, and now his posts make up a majority of the entire website (not a joke).

Blogs

I hope to see some of you at the Progress Conference in Berkeley in October. Applications close May 15th.

There are also still some spots left for undergraduate and graduate students to go to the Public Choice economics conference in George Mason University at the end of the month.

In last month’s post, I falsely stated that Catholics can be excommunicated for betting on the outcome of a papal election. Like a fool, I had forgotten about the Canon Law Reforms of 1917, which repealed all previous papal legislation that was not explicitly retained (including this excommunication rule).

The Éire Ventures microgrants programme.

The campaign to host the 2068 Olympics in Cork:

With hourly landings at Donegal space port, you can then take a silent autonomous flying car down the scenic west coast, directly to your apartment room.

There are also plenty of supersonic flights with similar flying car services from any of Ireland’s 53 airports.

Cork’s new hydrofoil port is also a great option for anyone coming from places like the Extended Sovereign Azores.

Notice the Ogham.

Last month, I mentioned my positive feelings toward Tyler Cowen’s academic philosophy work, which he writes more reflections upon here.

On whether the use of tariffs for “national security” violates World Trade Organization treaties.

When Paul McCartney met Bertrand Russell. GPT-o3 helped me track down that this occurred in June of 1966, meaning that Russell would have been 94, not 92 as the article states:

[Russell] just clued me in to the fact that Vietnam was a very bad war, it was an imperialist war and American vested interests were really all it was all about. It was a bad war and we should be against it. That was all. It was pretty good from the mouth of the great philosopher. “Slip it to me, Bert.”

I was recently asked to contribute a puzzle for an American midwest logic tournament, which for some reason was Moby Dick themed this year. Here was my contribution:

(a) Captain Ahab has two children, and at least one of them is a boy. What is the probability that both children are boys?

(b) Captain Ahab has two children, and at least one of them is a boy born on a Tuesday. What is the probability that both children are boys? (Assume children are equally likely to be born on any day of the week.)

(c) All children have a 10% chance of growing up to become whalers. Captain Ahab has two children, and at least one of them is a boy who will grow up to be a whaler. What is the probability that both children are boys?

How – and why – are all these answers different?

I also contributed this question to a different section:

A sheet of metal with a circular hole of radius 1cm is heated uniformly. Will the radius of the circle go up, down, or stay the same?

The evolution of Sit Club.

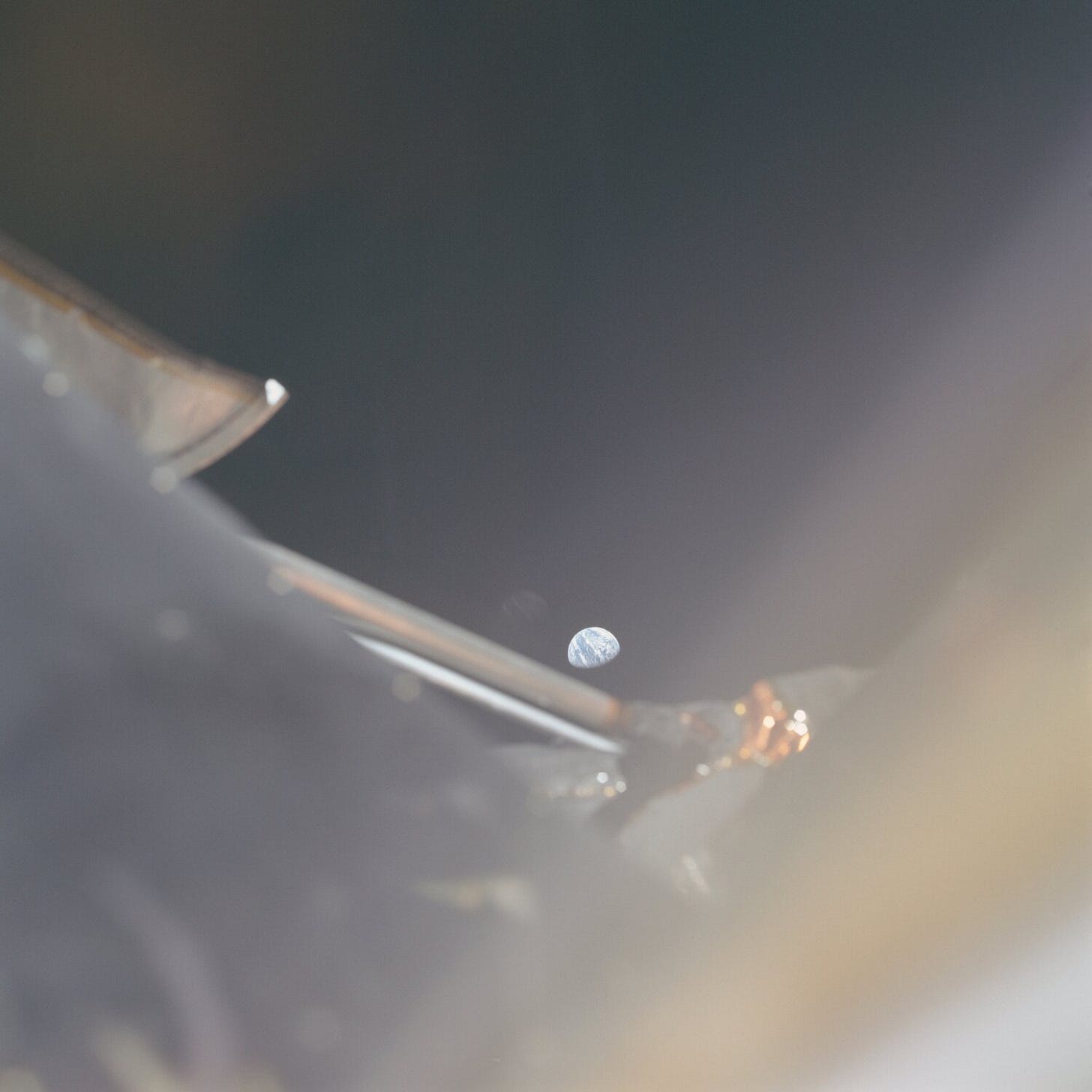

The Earth Restored: An archive of the best photos ever taken of the Earth from space. This is a side project of the Oxford philosopher Toby Ord. I found this project to be incredibly moving, and teared up while browsing. I had never seen the Apollo 17 Earthset photos. As Bill Anders said of Apollo 8:

We came all this way to explore the moon, and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.

I love this one taken from the Apollo 11 lunar lander:

The details about the gear are great too: all the photos taken by the Apollo astronauts were shot with Hasselblad cameras. My fellow space kids will also know that the astronauts all wore Omega Speedmasters.1

Kenneth Arrow reviews the selected essays of Frank Ramsey. Some new learnings: Ramsey showed in his first (!) article that, by appropriately reformulating the hierarchy of types, you can make most of the axioms from Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead’s Principia Mathematica redundant.2 I somehow missed this when reading the Mistak biography. It never ceases to astonish just how visionary Ramsey was. According to Arrow, there is very little in Savage’s famous 1954 formalisation of expected utility theory that was not already in Ramsey’s Truth and Probability.

What Harsanyi’s aggregation theorem does and doesn’t say.

This month, I enjoyed reading Ben West’s blog, which is now deleted and must be accessed through the Internet Archive. Here he is on esoteric mathematical questions that are sometimes relevant in ethics. He also taught me that all of the divisibility tricks are special cases of the same theorem. Elsewhere, Ben solves infinite ethics.

I have a new favourite pen, in the form of the blue 0.7mm Pilot FriXion. I missed the memo that erasable pens have gotten so good that there is no (?) reason for regular pens to exist anymore for everyday use. For the first time, I even had someone compliment my handwriting recently, which would have astonished my dyspraxic childhood self. These pens will be my go-to Christmas stocking fillers going forward.

The story of Viktor Zhdanov, the Ukrainian virologist responsible for the smallpox eradication campaign. I have stickers of him on my phone and laptop to show my support.3

The 84-year-old Herbie Hancock is perhaps the last of the all-time greats in jazz who is still performing. However, he hasn’t released a new studio album since 2010, because he can’t stop going down YouTube rabbitholes. And, one of my favourite clips: Miles Davis gets angry at Herbie in Milan, 1964.

Claude Shannon, the father of information theory, once built a computer that operated on Roman numerals, and it was called THROBAC. If I’m ever in Boston, I’ll be sure to visit it at the MIT Museum.

What Alvardo de Menard has been reading. Particularly strong in the ‘letters between lovers’ category.

Jose Luis Rícon links. [Edit: Link fixed now, thanks CW.]

Paying strangers from the internet to sit behind you watching you work as a productivity aid. What this tells us about the culture and emotional health of San Francisco is left as an exercise to the reader.

Minji Kim, a delightful former student of mine from Seoul, now has a blog.

Socratica Symposium, the film.

Dynomight on how to use paper. I love paper. I print so many essays and journal articles that, according to my printer’s analytics, since starting university, I have used an entire tree’s worth of paper (~500 separate jobs). I anticipate that the amount of paper I have lying around will become more manageable once my Daylight Computer arrives, but it’s been delayed by the goddamn tariffs.

Ronan Lyons, the doyen of Irish urban economics, has been made full professor and Fellow.

In 1963, the municipal government of London was substantially restructured, creating the concept of Greater London, which is divided into 32 boroughs and (separately) the City of London. In a twist of fate, the earliest appearance on film of a map of Greater London was in the Beatles’ music video for Help!

Diplomacy in the 21st century: Paddington rides the bullet train.

The new Monty Hall:

You are playing the Monty Hall problem. However, you secretly know one of the goats is the former pet of an eccentric billionaire who lost it and is willing to pay an enormous amount for its return, way more than the car is worth. You really want that goat. The host is unaware of this. After you pick the door, as is traditional, the host opens one door, which he knows doesn’t have the car. He reveals a goat, which you can tell is the ordinary goat and not the secretly valuable one. The host offers to let you switch doors. Should you?

After reading the essay from last month about mortality estimates for the Black Death, I went down a rabbit hole about the name ‘The Black Death’, which did not appear in English until 1755. How common are such retrospective renamings of historical events?

Here is a link to my GPT-o3 conversation about all the financial crises that were once known as ‘The Great Depression’. My pet theory is that one reason why so few people know about the 1893 recession is that it used to be called The Great Depression, and a memorable name never caught on to replace it.4

It’s always nice to see that Patrick is Hanseatic League-pilled.

Gavin Leech: You can just do things, but most of you should not.

I have learned that the ‘age of majority’ at which you are legally considered an adult in the United Kingdom didn’t drop from 21 to 18 until 1969. This explains a lot about memoirs of Victorian childhoods.

Which Bach Cantata? Hat-tip Jamie Rumbelow.

In 1989, only 3% of Americans had a valid passport. Crucial context is that Americans didn’t need passports to travel to Mexico or Canada until 2007, which in itself I found surprising.

Merge Club is hiring for a curator-in-residence, and the description sounds… extremely similar to what I already do for free. I DM’d the fellow, but no reply.

Which of the Great Books should ambitious 14-to-17-year-olds read?

James Somers has declared that the “word of the day” is a wasted genre, and has helped create Bracket City.

Podcasts

Inside the Good Friday Agreement.

Ian Leslie on John and Paul’s songwriting partnership.

Hibernian dominance continues: Morgan McSweeney, a Corkman, is the chief of staff for Keir Starmer, and is probably responsible for him becoming prime minister. He remains mysterious – there is supposedly only one recording of his voice – but over a period of years, he has ruthlessly purged the hard left and other political enemies from the British Labour Party. Conspiracy theories about the Irish never seem to have caught on the way they did with the Jews, but there really is quite a lot of source material to go on.

The episode above is from Inside Politics by the Irish Times, which is probably the podcast that I have listened to the most without ever including it in a links roundup. The host is great at what he does, but I can’t honestly recommend the subject matter. However, friend-of-the-blog Barra Roantree did recently appear on it to talk about the amount of regulation and red tape that Ireland imposes on construction.

Colm Tóibín on the Irish famine. Here is his long London Review of Books essay on the same topic. Colm repeats the urban legend, that I also learned in school, that Sir Walter Raleigh brought the potato to Ireland.

The history of relations between China and Cambodia. The China History Podcast is such a gem.

Scott Alexander’s first podcast appearance. And here is the AI 2027 scenario.

The “Beiping model” for a Chinese takeover of Taiwan.

Michael Huemer on building a philosophical world-model.

The story of the Chinese survivors of the Titanic.

Sheilagh Ogilvie on epidemics and the long-run history of institutions.

Joseph Carlsmith on controlling the AGIs.

Richard Dawkins on science education and the evolution of the reed warbler. It’s dispiriting that Dawkins says that most of the people who interview him on stage haven’t even read his books the whole way through.

Beijing in short fiction.

Books

A.W. Moore, The Infinite. A history of the concept of infinity, and the mathematical and philosophical puzzles it has engendered. The author defends finitism, although I didn’t fully follow his argument. He relies upon Wittgenstein’s idea that some concepts can be shown but not said.5

I liked this quote featured in the preface, from Michael Dummett, about the urge to constantly rewrite drafts, and why he included papers in a published anthology without any revisions:

It is not because I am wholly satisfied with everything contained in these essays that I have adopted this policy of not attempting to improve them: it is, conversely, because, once the process of emendation had been initiated, it would have been hard to bring it to an end… Any attempt by [a] writer, years later, to convert [one of his essays] into an expression of his present way of looking at the topic will produce only a mutilated object, representing neither his former nor his present view: he must either leave it as it stands, or write a completely new essay on the subject.

I feel the same way about my old WordPress blogposts. This was relevant because I read the third edition, in which Moore backtracks on several of his positions and is notably more influenced by Wittgenstein and by continental philosophy. The Infinite was also greatly influenced by Philip Turgetsky, and commissioned for the same series as his book about the philosophy of time, which I got absolutely nothing out of. Despite all this, I actually quite liked the book. I found myself nodding along merrily to a lot of vague and confusing claims of the sort I usually hate. Yes: To understand the foundations of set theory, we must first read Deleuze (?).

I also learned from this book about John Lucas, who was beating the drum long before Roger Penrose that Gödel’s incompleteness theorems imply that the computational theory of mind is false. If I were to win the Nobel Prize in Physics, or another prestigious scientific award, I would gather together a council of my friends so that we could decide which borderline-crank theory of consciousness I would spend the rest of my life promoting. Integrated information theory is the current front-runner.

Amanda Askell, Pareto Principles in Infinite Ethics. While not technically a book, this is more than long enough to be on this list. I think this is the second time I’ve read someone’s PhD thesis from cover to cover, which was two more than I was expecting.

This thesis has the most fucked bibliography I’ve ever seen. It’s possible this is not the actual document she graduated with, and there may be an incorrect LaTeX package installation going on. But there is really rather a lot of sloppy typography and confusing referencing. Pages 191 and 196 contain the same footnote reprinted almost word for word, and the examiners don’t seem to have noticed. I found this surprising, given that I heard that New York University is one of the most prestigious and rigorous philosophy departments in the world, usually outranking the Ivies.

In any case, I wrote a paper about this, which contains more detail than probably anybody cares about. I came away quite sceptical of the arguments from the effective altruists that ‘infinite ethics’ is a particularly deep or important problem. It seems to mostly be an issue for moral views that I didn’t find particularly plausible to begin with. Askell’s arguments (chapter 5) for why infinity is a major problem even for virtue ethics and Kantianism are particularly weak. At least some of it seems to come down to quite handwavy allusions to “impossibility theorems”, the mathematical content of which I’m not convinced the infinite ethics authors have actually understood. It is one intellectual puzzle among many, albeit one I think is cool and at least somewhat tractable, or else I wouldn’t have written the paper.

Askell, by the way, is now doing interesting alignment work at Anthropic: she is a coauthor on the Language Models are Few-Shot Learners paper. May she serve as a beacon of hope to all aspiring AI philosophers in the Bay Area.

George Boolos, Richard Jeffrey, Computability and Logic (3rd edition). This book is one of the rare cases where the edition really matters. I was told by a professor that the style completely changed between the 3rd and the 4th edition, so drastically that he was baffled it wasn’t re-released as a different book. Between editions three and four, one of the coauthors died, and they picked up a new one. Chapter 2 has a quote that made me chuckle:

Vivid talk of lists and superhuman enumerators may still aid the imagination, but in such terms the theory of enumerability and diagonalization appears as a chapter in mathematical theology. To avoid treading on living toes we might put the whole thing in a classical Greek setting: [Georg] Cantor proved that there are sets which even Zeus cannot enumerate, no matter how fast he works, or how long (even, infinitely long).

It’s a shame they didn’t mention the story about how one of the first things that Cantor did after discovering the transfinite numbers was to write to the Vatican to ask them to check it for heresy. He wasn’t even Catholic! Theologians have now had over a century to puzzle over whether there is an order of infinity so large that not even God can count it.6

Some of this book is fairly fiendish, and I won’t pretend to have understood most of it. One of the exercises in chapter 3 is essentially equivalent to the Busy Beaver problem, and chapter 4 is about why completing the previous exercise is impossible. I mentioned the Busy Beaver sequence in a previous post; I haven’t gotten a chance to read Scott Aaronson’s survey of the frontiers of Beaverology yet, but I’m sure it’s good.

The book is dedicated “For Rebecca and Edith”. Whenever I see an incredibly niche book being dedicated to someone who may or may not understand what the subject matter is, I’m reminded of the story of Queen Victoria meeting Lewis Carroll, and telling him that she loved Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland so much that she’d like his next book to be dedicated to her. He complied, but, being a mathematician, his next book was called An Elementary Treatise on Determinants. Sadly, this story is apocryphal.

I mentioned in my review of the infinitely more readable Annotated Turing that “almost everybody” believes that the Church-Turing thesis is true. If I’m understanding correctly, the early chapters of this book were assembling evidence in its favour: There are many different superficially different ways of defining the class of computable functions, and so far, no one has found any which contains a function outside the Turing computable class. This book explains three: abacus machines, recursive functions, and Turing machines.

This is actually the reason why Alan Turing’s original paper was published at all. His main result was scooped by an American, Alonzo Church, but they proved it in ways that were so fundamentally different that Turing’s approach was still considered publishable. The Turing-computable functions are the same as the functions which are definable in Church’s lambda calculus (one of the lambda operators, the Y Combinator, gives its name to the famous startup incubator).

Chapter 27, on the modal logic of provability, was the most engaging, although I hesitate to use the word “fun”. It’s a rite of passage at “ratcamp” to learn about Löb’s theorem, of which provability logic is an application. The footnote on page 273 led me down a rabbithole about Krister Segerberg, who appears to have been the great Swedish logician of modern times, and who passed away earlier this year. His PhD thesis is a classic (!) in the field of modal logic. He wrote a paper about infinite ethics in 1976, which remained in obscurity until Nick Bostrom popularised the idea. May he rest in peace.

Michael Huemer, Justice Before the Law. The first book of legal philosophy I’ve read. For me, Huemer is a guilty pleasure. His basic thesis is that the state has no particular authority to do anything that a private individual would not, in theory, be morally justified in doing. And so the law is only justified insofar as it leads to a better outcome in a particular case. Strongly contrary to the widespread view of legal positivism, Huemer thinks that we should nullify juries, disobey court orders, and search for pedantic loopholes as much as possible in order to circumvent immoral laws. Huemer is on record as a Shakespeare hater, but he should really read The Merchant of Venice – so much of this is in there!

The part of this book that was most novel to me was about how the idea that juries are only supposed to give their judgment about whether a defendant is guilty is a modern fabrication. At least in the Anglo-American tradition, from the beginning, juries were explicitly set up as a check on immoral laws and excessive state power (page 304).

Alas, any such role that juries once played in America is now much diminished. An astonishing 97% of criminal trials end in plea bargaining, which often involves defendants pleading guilty to crimes no one involved even thinks they committed (page 113). It’s depressing that this status quo is so widely accepted, especially by judges. Most of the American criminal justice system is essentially blackmailing people into confessing to crimes that, in many cases, they haven’t even been accused of committing.7

I am curious if Huemer has ever served on a jury and, if so, whether he used it to implement his ideas. I was called for jury duty for the first time last year, but had it deferred for educational reasons.

See page 339 for a debunking of the debunkings of the Milgram electric shock experiment:

Unfortunately, it has recently become popular, when the Milgram study is mentioned, for lay people to claim that the study has been debunked, referring to Perry et al. (2020). Perry et al.’s paper is sometimes misreported as showing that the obedient subjects “did not believe” that they were really electrocuting the learner. In fact, what Perry et al. report is that most subjects, after the fact, claimed to have been less than fully certain that they were really electrocuting the learner, and that the people who had fully complied reported lower certainty on average than the people who had disobeyed the experimenter. Nevertheless, 74% of the fully obedient subjects reported that they had either fully believed that the shocks were real or had some doubts but still thought the shocks were probably real. Only 4% claimed to have fully disbelieved in the reality of the shocks (Perry et al. 2020, table 3). Note also that the obedient subjects may have lied after the fact about their earlier belief state, with the aim of making their behavior appear less reprehensible. If one genuinely thought that the shocks were not real, then one would have no reason for continuing the charade of pretending to shock the learner.

And Gavin Leech’s debunking of the debunking of the debunking:

[The Milgram experiment is] just not worth arguing about. It's an n=40 piece of shit from the armpit age of psychology.

I haven’t looked into the details of this Perry study, and I agree it sounds troubling. But defending the Milgram experiment is a strange hill to die on. The Oxford Handbook of Social Influence says that “Milgram’s interpretation of his findings has been largely rejected”, which I think is a fairly representative view.

Thomas Lin, The Prime Number Conspiracy: The Biggest Ideas in Math from Quanta. A collection of the best maths articles from Quanta Magazine. I also enjoyed their selected essays about the natural sciences, which also came out in 2018. I wish they would release more of these, although it seems they are now engaged in a similar venture in the form of starting a publishing company.

The book opens with some essays about Yitang Zhang and his influence. Zhang was an obscure figure at the fringes of academia who, in 2013, out of nowhere, proved that there exists a number less than 70,000,000 for which there are infinitely many primes separated by gaps of that size. Given that no one had ever proved the existence of a bounded prime gap before, this was one of the major mathematical discoveries of the millennium. This prompted a flurry of activity as mathematicians, including some amateurs, used his methods to decrease the bound. This is especially exciting, because, if you could get the bound down as low as two, you would have proved the conjecture that there are infinitely many twin primes. Thanks to efforts led by Terence Tao and others, the most recent effort I’m aware of has gotten the bound as low as 246. The whole saga reminded me a lot of another recent bound that was proved out of nowhere and followed by a flurry of activity, namely the incredible story of superpermutations.

I adored this essay about June Huh and his friendship with the legendary Japanese Fields Medalist Heisuke Hironaka, who convinced him to switch fields from poetry (!) to mathematics. Note this is separate from another essay about June Huh I’ve linked to before, which was written a few years later, after June himself won the Fields Medal.

I hope that one day I’ll be able to throw parties that are as fun as Freeman Dyson’s 90th birthday:

The next year, [William] Press traveled to Princeton, New Jersey, for a two-day celebration of Dyson at the Institute for Advanced Study, Dyson’s intellectual home for the past six decades. In honor of Dyson’s 90th birthday, there was seemingly boundless cake, a forest of long, white candles, 350 guests—including his 16 grandchildren—and lectures recognizing his eclectic achievements in math, physics, astronomy and public affairs. H. T. Yau of Harvard University commenced the math section, launching into Dyson’s work on the universality of random matrices. George Andrews of Pennsylvania State University and Kathrin Bringmann of the University of Cologne followed with the implications of Dyson’s early contributions to number theory, which he began contemplating in high school.

Papers

Carl Christian von Weizsäcker, Existence of Optimal Programs of Accumulation for an Infinite Time Horizon. If any of you have studied economic growth at a graduate level, you will have come across the Ramsey-Cass-Koopmans model. This is a modified version of the model from A Mathematical Theory of Savings (1928), which is concerned with optimal growth rather than savings, and about competitive economies rather than the social planner’s problem. One of the problems with these models is that if you don’t have some kind of discount rate for the welfare of future generations, you get an infinity paradox when trying to compare indefinitely long possible future utility streams. And the idea that we should discount the welfare of future people merely because they live in the future seems ethically indefensible. In my understanding, it was worked out in the 1960s that, under certain conditions, you don’t actually need to have all the discounted future utilities sum to a finite value for there to still be an optimum strategy for how to allocate resources across time in these models. But it turns out to be highly non-trivial to figure out exactly what that set of conditions is. I think this is what this paper is doing, but it was very complicated, and I didn’t really follow.

Harris Nover, Alan Hájek, Vexing Expectations. A major result of mathematical analysis is Riemann’s rearrangement theorem. This says that if you have a conditionally convergent series, then by choosing what order to add up the terms in, you can get it to converge to whatever number you want, or to have it diverge to positive or negative infinity. This paper describes a case where the expected value of an action is given by a conditionally convergent series. Because a rational decision-maker can choose to sum up the values in a different order to get whatever answer they want, the expected value is completely undefined. The authors consider, and reject, the idea that the passage of time somehow defines an ‘essential natural order’ in which the values are to be considered. Hájek has later work developing the idea that this is not a problem because we intrinsically need to know how to evaluate such an implausible case, but because, if you ascribe any nonzero probability to currently being in such a scenario, it blows up your whole decision theory.

I think this is a much deeper and more interesting problem than the St. Petersburg paradox. The trouble in that case is over whether a series of bets is infinitely good, where everybody agrees that it is good. But for Nover and Hájek’s ‘Pasadena Game’, nobody even knows whether it’s good.

You can also listen to Hájek talk about more puzzles of probability on the 80,000 Hours podcast.

Peter Diamond, The Evaluation of Infinite Utility Streams. Diamond’s theorem is historically important in economics, but seems to have been forgotten a bit. Or at least, that is my impression from the fact that ChatGPT didn’t even rate it as being in the top 5 most famous theorems called Diamond’s theorem. What it’s saying is that you can’t have a cardinal social welfare function which compares infinite utility streams that is complete and obeys the assumptions of ‘Finite Anonymity’, ‘Strong Pareto’, and ‘Continuity’. So: If you’re assigning a number to how good any infinite utility stream is overall, which doesn’t care if you make irrelevant permutations between equally well-off people (Anonymity), respects that making one person better off while making no one worse off is an improvement (Strong Pareto), then that function must sometimes jump around wildly given tiny changes in inputs. It turns out that you can still get Diamond’s theorem to work under a weaker set of assumptions, so it’s mostly of historical interest. But different papers use inconsistent terminology for these different assumptions, so the above took me ages to figure out. Going through the major papers in this literature to try to standardise the notation for a project I was working on was one of the more tedious things I’ve done in recent months.

Matthew Adelstein, Alternatives to the Self-Indication Assumption Are Doomed. Congratulations to undergraduate blogger Bentham’s Bulldog for having a philosophy paper published in a peer-reviewed journal.

The two main approaches in the field of anthropic reasoning are called the Self-Sampling Assumption (SSA) and the Self-Indication Assumption (SIA). SSA says that you should reason as though you are randomly sampled from the set of all observers in your reference class. SIA says that you should reason as though you are randomly sampled from the set of all observers that could be in your reference class. Nick Bostrom defends SSA, which means that he accepts that the Doomsday Argument is true and believes ½ is the correct answer to the Sleeping Beauty problem. Joe Carlsmith defends SIA, which means that he rejects the Doomsday Argument and believes ⅓ is the correct answer to Sleeping Beauty.

Mr. Bulldog has waded into this debate with some new arguments for why SIA is the only live option. As I understand it, he’s saying that the main argument against SIA is the “Presumptuous Philosopher”, which is that SIA’ers think that philosophers can, in many cases, determine which physical hypotheses are true completely a priori, because of its bias toward explanations in which a larger number of observers like yourself will exist. Matthew says that every alternative to SIA must also bite this “presumptuousness” bullet. Nobody has come up with a view in which you can avoid such theoretical philosophical concerns being relevant to evaluating which physical hypotheses are true.

Recently, Matthew has gone full Frank Tipler, and said that, because SIA is true, we have infinitely strong reason to believe that infinitely many observers exist. And you know who would create every possible observer? Only an omnipotent, benevolent God. What started as an innocent question about how to apply Bayes’ rule to calculate the probability that a coin will come up heads has ended in the most gigabrain argument for monotheism I’ve ever seen.

Toby Ord, Hypercomputation: Computing More Than the Turing Machine. The Church-Turing thesis is widely misunderstood:

Turing describes an effective procedure as one that could be performed by an idealised, infinitely patient mathematician working with an unlimited supply of paper and pencils – but without insight. It is this that he says is equivalent in power to the Turing machine. He does not deny that other models of computation could compute things that Turing machines cannot. He does not even deny that some physically realisable machine could exceed the power of a Turing machine

Similarly, you can get violations of Gödel’s incompleteness theorems if they are instantiated in the right physical system. Gödel himself believed that his results did not put a limit on human reasoning.

This might be Toby Ord’s most interesting and impressive paper, and it was his undergraduate dissertation! Amazing…

David Cass, Optimum Growth in an Aggregative Model of Capital Accumulation. One of the reasons why Ramsey’s early work on optimal savings was not widely understood was because it relied on methods from the calculus of variations, which at the time would have been considered incomprehensible by most economists. Cass reworked some of these ideas based on the calculus of variations work by Pontryagin, the blind Soviet mathematician. I didn’t fully follow, but Cass himself said that much of his research was just rediscovering what had already been worked out by Ramsey almost 40 years earlier.

Luc van Liedekerke, Luc Lauwers, Sacrificing the Patrol: Utilitarianism, Future Generations and Infinity. I’ve never come across someone called Luc, let alone two of them. I didn’t find this paper particularly engaging: the best part is a footnote on the final page, and their title metaphor is somewhat tortured. Their explanation of the history of midcentury macroeconomics (p.160) also seems a bit sloppy to me.

Adam Jonsson, Mark Voorneveld, The Limit of Discounted Utilitarianism. I… kind of think these guys solved infinite ethics???

The authors’ approach is to apply methods from dynamic optimisation theory to look at the behaviour as you take the limit as the social discount rate goes to zero.8 They use that to define a social welfare function for ranking infinite outcomes that has much nicer properties than anyone has managed to get it to have so far. Typically, there are certain impossibility theorems which show that we can’t specify a social welfare function which has certain reasonable-sounding properties. This is the most convincing attempt I’ve seen to loosen the ‘completeness’ constraint without biting some pretty horrific bullets. The upshot here is that if you embrace a tiny amount of discounting, which won’t matter for any practical purposes, you will be able to rank, in a well-behaved manner, many more infinite utility streams than anyone (?) previously thought possible. Here, a ‘utility stream’ is just a stand-in for an infinite sequence of numeric values.

Kenny Easwaran, A New Method of Value Aggregation. Kenny Easwaran seems a nice fellow. His appearance on the Rationally Speaking podcast was probably the first time I ever heard about Newcomb’s problem, back when I was a wee baba. He does, however, seem to be one of those people who complains about philosophy having too much maths, but really just wants to replace it with different maths:

They fetishize certain mathematical operations, in a subject that is not inherently mathematical.

His paper discusses the implications of the axiom of choice, and is a sequel to another, about modifying decision theory to rid it of representation theorems.

Since I’m finishing up my undergrad, I’ve been thinking a lot recently about the purpose of philosophy, what it means to have good philosophical ‘taste’, and so on.

I hear a lot of people who should know better making deepities about how these esoteric philosophical puzzles aren’t real. The problem, they say, is not in the world, in your oversimplified model of the world. And I feel like saying: Mate, obviously the problem is in the model! Were you expecting the contradiction to be in reality itself? The problem is that nobody can get any of the models to work. (Whether these puzzles matter in any practical way is, of course, a completely separate issue.)

Maybe I’ve become a curmudgeon, but I’m coming to the view that outsider critiques of academic disciplines are >97% utterly irredeemable rubbish. Almost all outsider critiques of economics are such ridiculous strawmen as to not even be worth naming. The best example I knew of, Joe Studwell on the East Asian growth miracle, while tremendously interesting and stimulating, is not holding together in the details (see some of my recent discussion of land reform in Taiwan).

And following the above, almost all critiques of philosophy I have seen fall into the following two buckets:

The above trivial point about the problem being with the model, not with reality.

Dogmatically asserting some naive philosophical position as true.

What did you think philosophy was going to be about? Vibes? Papers? Essays? Yes, that is what it’s about.

Music

Mahavishnu Orchestra, The Essential Mahavishnu Orchestra. My favourite is Vital Transformation. I’ve listened to a lot of John McLaughlin, but I’m only now exploring his bands Mahavishnu Orchestra and Shakti.

Shakti, Natural Elements. Amazing tabla from the late great Zakir Hussain. One of the songs on this album is the origin of Shruti’s blog title.

Wings, Goodnight Tonight. A single that is sometimes described as Paul McCartney’s ‘disco record’. Recorded as part of the Back to the Egg sessions, but not released as part of the album. See here for some analysis of the bass line.

Herbie Hancock, My Point of View. Hancock’s second album for Blue Note Records. Many of my favourites are here: Hank Mobley on tenor saxophone, Tony Williams on drums, Grant Green on guitar. Herbie Hancock was the exact same age as me when he released this album – frightening! Like a fool, I didn’t secure tickets to see him at The Barbican this summer before they sold out.

Beethoven, Piano Concerto No. 3. I greatly look forward to listening to the South Korean pianist Yeol Eum Son perform this next week. You can watch her play Chopin's Piano Concerto No. 2 here. Supposedly, Beethoven’s 4th and 5th piano concertos are widely regarded as the best, although the first was most striking and memorable to my ignorant and untrained ears. On the classical music front, I also continue to slowly work through The Rest is Noise by Alex Ross and his associated listening guide.

I struggle to listen to music with headphones nowadays because I have worsening tinnitus. A few days ago, I had another of my hypochondriacal visits about it to an audiologist. I felt a pang of pride when he made me look away from the testing device because he thought I might be cheating. Almost no one at the clinic had ever had such excellent hearing. If anyone has had notable success in dealing with psychosomatic tinnitus, let me know.

Films

Again, too busy to watch any films this month, but I do have some recommendations from YouTube:

A new series is beginning on applied complex variables. See my old guide to my favourite maths channels. And: Why is DeepSeek’s version of the transformer architecture so much more computationally efficient? You can even buy a poster of the Multi-Head Latent Attention mechanism, for the machine learning lovers in your life.

Will Trump succeed in killing the penny? (PS: I believe this is my first use of the T-word in any piece of public writing.)

Terence Tao on the cosmic distance ladder. Here is the associated FAQ. I thought this series was phenomenal, a real highlight of the genre. Elsewhere, Grant Sanderson explains the inscribed square (and rectangle) problem.

Finally, Edward Teller talks about the genius von Neumann.

Upon reflection, I’m not sure I qualify as having been a space kid anymore. I mistakenly thought that all the Apollo astronauts wore the Omega Speedmaster 3, i.e. the 105.003 model. But not many of them wore that particular type, which became famous because it was the first watch to officially qualify for use in space. The Speedmaster 3 was used on the Gemini missions, including by Ed White on the first American spacewalk.

For the programmers among you, type theory is derived from the ‘logicist’ system that Russell and Whitehead created.

Much as I hate to cede an inch to the Americans, the official spelling of the World Health Organization is with a z, not an s, as this article incorrectly states.

He puts it too strongly, but this is what Peter Turchin has to say about it:

“No depression had ever been as deep and tragic as the one that lasted from 1893 to 1897. Millions suffered unemployment, especially during the winters of 1893-4 and 1894-5, and thousands of ‘tramps’ wandered the countryside in search of food . . . Despite real hardship resulting from massive unemployment, well-being indicators suggest that the human cost of the Great Depression of the 1930s did not match that of the “First Great Depression” of the 1890s . . . Furthermore, while the 1930s are remembered as a period of violent labor unrest, the intensity of class struggle was actually lower than during the 1890s depression. According to the US Political Violence Database . . . there were 32 lethal labor disputes during the 1890s that collectively caused 140 deaths, compared with 20 such disputes in the 1930s with the total of 55 deaths. Furthermore, the last lethal strike in US labor history was in 1937…in other words, the 1930s was actually the last uptick of violent class struggle in the US, superimposed on an overall declining trend.

The 1930s Depression is probably remembered (or rather misremembered) as the worst economic slump in US history, simply because it was the last of the great depressions of the post-Civil War era.”

The saying/showing distinction has attracted a lot of attention and criticism. Frank Ramsey famously said that “What we can’t say we can’t say, and we can’t whistle it either”, which also referenced Wittgenstein’s habit of whistling complex operas while walking around Cambridge. I can’t tell if this means he thought it was good or bad, though.

I thank GL for alerting me to this amazing story.

I tried to find statistics on how common such “fictional pleas” are, but it seems like they’re so widespread that nobody is even collecting statistics about it: “Fictional pleas are pervasive. Every defense attorney I talk to says they happen so much they just call them pleas. It’s not even worth naming. They’re the norm, not the exception.”

Strictly speaking, they compare infinite utility streams by taking the limit inferior of the discounted differences between them. ‘Limit inferior’ in this context means that, if the streams oscillate relative to each other forever, their model considers the least of the accumulation values (values hit infinitely often). The purpose of this is to create a more stable and conservative ranking, but it’s a controversial choice.

re The Economist spam, what worked for me before was sending a complaint to their privacy email, dataprivacy@economist.com. (Then I did have to use another ridiculously clunky online system, but eventually the emails stopped coming...)

In Australia you can subscribe for free to The Economist via your local public library via Pressreader App